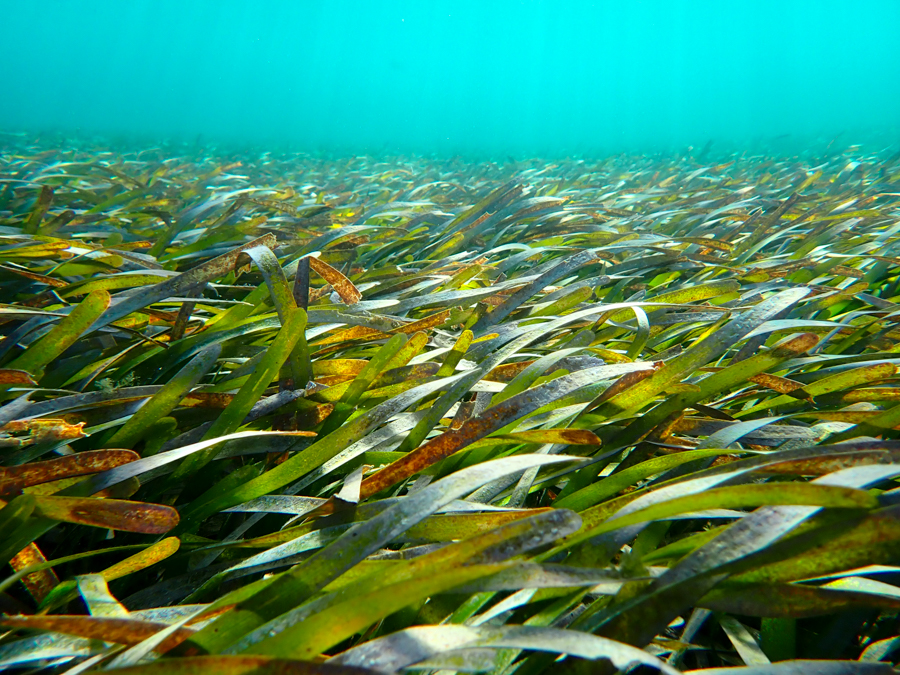

If you ask someone “Why do fish school?” you will likely get “to avoid predators” for an answer. After all, the more eyes you have watching the harder it is for anything to sneak up on you. Furthermore, if a predator does manage to attack, each individual fish in a large group has fairly low odds of being the one who gets eaten. Diving the Great Barrier Reef has, however, given me cause to ask a slightly different question: Why are so many predatory fish schooling too?

During the course of this trip I have encountered large schools of snappers, grunts, barracudas, and jacks. The jacks make the best photographic subjects because they appear completely un-intimidated by divers or air bubbles, although being surrounded by a school of fifty giant trevallies can be a bit unnerving.

Bigeye jacks showing no fear of a diver’s bubbles.

It turns out there are several good reasons for fish to school even if they are high on the food chain. Hanging out in schools gives fish access to plenty of attractive mates, which explains why some of the jacks I have seen have displayed the characteristic dark spots of males looking for a suitable mate.

School of barred jacks with males showing dark spots.

Schools also, unsurprisingly, provide learning opportunities as fish can become aware of new food sources and how to hunt them by copying each other (Takahashi et al. 2014). A group of predators is also more successful at attacking schooling prey than a single predator would be attacking alone (Handegard et al. 2012). Finally, schooling by predators may be part of a competitive arms race between various species. The aforementioned giant trevallies I saw successfully chased a school of about thirty chevron barracudas off the reef.

The school of giant trevally that chased off the barracudas.

Of course, it also is possible that even scary predatory fish species like giant trevallies and chevron barracuda actually school because they are afraid of an even greater predator. I, however, prefer not to think too much about this possibility given the amount of time I spend in the ocean.

School of barred jacks evidently less interested in breeding.

Sources:

Handegard NO, Boswell KM, Ioannou CC, Leblanc SP, Tjestheim DB, Couzin ID. 2012. The dynamics of coordinated group hunting and collective information transfer among schooling prey. Current Biology 22, 1213-1217

Takahashi K, Masuda R, Yamashita Y. 2014. What to copy: the key factor of observational learning in striped jack (Pseudocaranx dentex) juveniles. Animal Cognition 17, 495-501

Photos by Abigail Cannon.