On each of today’s three dives, like all the others, the first thing Alexandra Dempsey does when she reaches the bottom is to pull out a plastic container about the size of a Nalgene water bottle, scoop it full of sand and tuck it away in a pocket before swimming off to other duties. These sediment sample collections are just one part of the expedition’s benthic (seafloor) research, led by Alex, Andy Ross and Rachel D’Silva.

When she returns to the Golden Shadow, Alex takes her bottle of wet sand to the lab and replaces the salt water with a solution of diluted bleach to neutralize any biological material. The bottles of sediment sit on a shelf until the expedition is over

Back on shore Alex dries each container-full of sediment under a low heat lamp. Then she puts them through a machine called a CAMSIZER, which analyzes the sizes and shapes of the particles.

It’s important to know as much as possible about the sediments of each area the expedition visits. Sand is constantly moving around the seafloor, and too much can bury young coral recruits or even adult corals, almost as if they’re being suffocated. “It’s important to see where the sediment is accumulating and where it’s coming from,” Alex says. “Sand shifted in large enough quantities can affect the resilience of reef and how well it can regenerate.” Currents can do it, but so can fish like parrotfish, who nibble on coral and excrete it as powder.

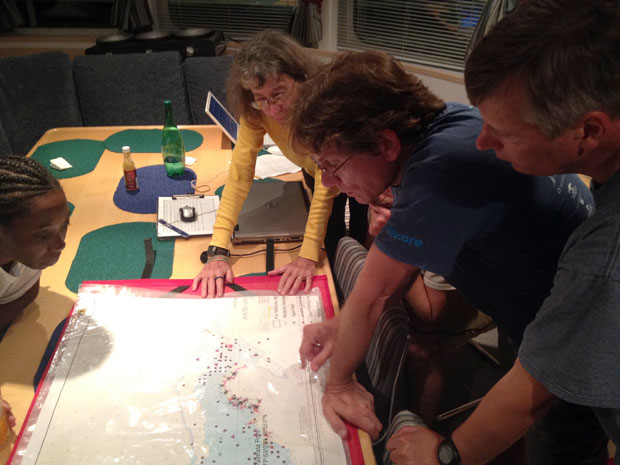

After collecting the sediment samples, Alex’s other job is to survey the seafloor along with Rachael and Andy (benthic surveys). They each roll out a 10-meter (33-foot) weighted line, marked every 10 cm (4 in) with a colored plastic nub. At every one of these 100 points, each researcher record what’s directly underneath it, using underwater pencils, paper and everyday plastic clipboards.

There’s a wide range of options, including hard ground, rubble, sand, algae, sponge, invertebrates, cyanobacteria, live coral (including species), and dead coral, further subdivided into recently dead, long dead, fully bleached, and so on. Before rolling up their weighted line, they also take a quadrat (a square of narrow PVC pipe) 25 cm (10 in) on a side, and lay it down every two meters along the line. If there are any coral recruits (baby corals) inside the square—and we always hope there are—those go on the data sheet too.

With so much competing for space on the seafloor, knowing what’s growing there—and what isn’t—can help measure the heath of a reef ecosystem, and how to help if it’s hurting. Healthy reefs are mostly coral in a range of species and sizes, with a small percentage of macroalgae (seaweed). These are normally kept small and sparse by grazing herbivores like parrotfish, surgeonfish and sea urchins.

When reefs are disturbed, though, macroalgae and other aggressive invertebrates, like anemones and certain gorgonians and sponges, are happy to move in and crowd out coral. If you fish out too many herbivores, for example, macroalgae can grow into carpets that trap sediment and kill coral. An especially good sign on the seafloor is a hard substrate—the only surface coral can settle on—covered with a crust of pink coralline algae, which acts as cement to hold the reef together.

(Photos/Images by: 1-2 Alexandra Dempsey, 3 Julian Smith)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members.