Fact Friday

Some cnidarians switch between a polyp and a medusa body form. Corals and anemones only have the polyp stage. Jellyfish, as we think of them, are in the medusa stage, but they have a polyp stage when they are juveniles. Hydrozoans have the opposite: their adult form is a polyp, but they have a juvenile medusa stage.

Photo Credit: KSLOF, Rob Martimbeault

Background Information

Reproduction

Reproduction is the process of creating offspring. Organisms must reproduce in order for their species to survive. How do corals reproduce? Remember that corals are sessile so they have to be creative when it comes to reproduction. In this unit, we will learn about different strategies that coral use to reproduce.

Corals reproduce by one of two methods:

- Sexual reproduction

- Asexual reproduction

SEXUAL REPRODUCTION

Let’s begin with sexual reproduction, the production of a new organism from two others of the opposite sex. This requires the production of sperm and eggs, which are often referred to as gametes. Gametes are mature sexual reproductive cells. The majority of coral species are hermaphroditic, meaning that they produce both sperm and eggs. The rest consist of separate sexes (male or female) meaning that they produce either eggs or sperm. When a sperm and egg combine to form a new organism it is called fertilization.

Fun fact

X

Fun Fact

Humans can do it, and now corals can too – freeze their eggs, sperm, and embryos for later usage. In 2010, scientists set up the first ever frozen bank for corals. Using techniques learned from human fertility, scientists have successfully figured out a way to preserve coral’s reproductive cells for many years to come. Currently, corals are under threat and their future is uncertain, probably dire. These scientists are planning ahead by cryopreserving different coral species just in case they need restore reefs in the future.

Check out the video about Dr. Mary Hagedorn’s work: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VUZMKLo-VoE

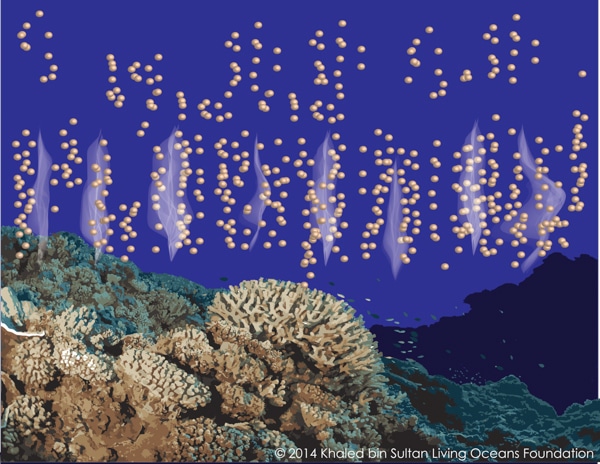

The majority of corals are considered hermaphroditic broadcast spawners, a type of external fertilization. Broadcast spawners, sometimes referred to as mass spawners or synchronous spawners, release both sperm and eggs into the water at the same time (figure 5-1). Some corals release buoyant egg and sperm bundles. These do not self fertilize, but instead, they float to the water’s surface where they break apart, releasing gametes, which then combine with those from other corals, completing the process of fertilization. Other corals fertilize the eggs internally in the gastrovascular cavity (see Unit 3: Coral Anatomy), and allow them to grow into planulae (see Unit 6: Life Cycle). These corals are called brooders.

Both of these are different reproductive strategies that have various outcomes. Can you think of the benefits and disadvantages of each of these strategies?

Figure 5-1. Mass spawning event where the round objects are eggs and the white clouds are sperm.

| Benefit to Spawners | Benefit to Brooders |

| More sperm and eggs released; safety in numbers | Fewer but better developed planulae |

| Carried in currents over greater distances; greater genetic diversity | Can settle immediately; less chance of getting eaten |

| Requires less energy | Can release planulae at any time because it is already in its planktonic stage |

| Disadvantage to Spawners | Disadvantage to Brooders |

| Longer distance = less chance of survival | Less genetic diversity |

| Have to get the synchronization correct for gametes to be able to reproduce | Requires more energy |

Some corals can actually use a combination of brooding and spawning in order to benefit from each reproductive strategy and ensure the survival of their species.

A mass spawning occurs when many different coral species synchronize the release of their eggs and sperm. Mass spawnings have been observed on coral reefs throughout the world. Usually the event occurs once a year; however, two spawnings have been documented. Additionally, in some areas, minor spawning events occur throughout the year. Generally, spawning events take place after a full moon during certain times of the year, dependent on location.

Here are a few examples:

- Great Barrier Reef, Australia; occurs in October or November and sometimes December, 4-5 days after the full moon (GBRMPA 2011)

- Western Australia; occurs in March or April, 4-14 days after the full moon (Babcock et al. 1994)

- Florida Keys; occurs in August or September, 3-5 days after the full moon (Szmant 1986)

- Flower Garden Banks, Gulf of Mexico; occurs in August, 7-10 days after the full moon (National Ocean Service 2014)

Other non-coral invertebrates have been observed releasing their gametes during the mass spawning as well, including sea stars, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, sponges, marine worms, and molluscs. Again, this reproductive behavior is beneficial by allowing a large amount of gametes to be present; therefore, the likelihood of an individual being eaten is decreased. This is sometimes referred to as safety in numbers. Even though there is a feeding frenzy by fish and invertebrates (figure 5-2), there are many gametes present and many will survive.

Figure 5-2. Brittle star feeding on coral’s gametes

In areas like the Great Barrier Reef, the spawn is so large that a pink slick of unfertilized eggs and embryos (fertilized eggs) can be seen on the surface of the ocean (see top banner).

Fun fact

X

Fun Fact

Can you imagine getting smashed by a wave and then you produce a clone? Scientists have found that after a mass spawning event, once embryos have formed, they do just that. The coral embryos are fragile, lacking a protective outer layer, and when they are hit by a large wave, they can break apart. Instead of dying, the broken embryo continues to produce more cells normally. They may be a little behind the curve in terms of size and development, but they appear to be able to settle and grow just like normal embryos. This is just one more reproductive advantage that corals can use to ensure survival.

Check out the planulae and settled coral polyps here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9WCBOhBW2Tk

Source: Heyward, A.J., and Negri, A.P. 2012. Turbulence, Cleavage, and the Naked Embryo: A Case for Coral Clones. Science (335) 6072: 1064.

Some corals are asynchronous spawners meaning that they can spawn during the mass spawn, but they are more likely to spawn before or after it. Different species spawn at different times.

There are certain environmental cues that tell corals when to spawn. It is unclear exactly which cues affect spawning events, though it is believed that corals respond to multiple environmental cues. What environmental cues do you think could affect spawning?

Here are some potential environmental cues:

- Sea temperature

- Salinity

- Storms and weather conditions

- Currents

- Latitudinal variation

- Day length

- Tidal cycle

- Lunar cue

- Chemical signaling

- Wind patterns

- Anthropogenic effects

As corals become more threatened by anthropogenic, or human produced effects, it is likely that successful coral reproduction will also be at risk (see Unit 19:Threats, coming soon).

ASEXUAL REPRODUCTION

The second way that corals can reproduce is via asexual reproduction. Asexual reproduction is a means of reproduction where a new organism arises from a single organism. This new organism will only have the genes of the parent organism and it is an identical clone of the parent. Corals use several different methods of asexual reproduction.

- Fragmentation: when a piece of coral intentionally or unintentionally (storms, human disturbance, etc.) is broken off from the parent coral. It can grow, developing into a mature coral and starting new colonies. This method is often used by people to restore coral reefs (figure 5-3). A fragment can be broken off, grown until they are healthy and mature enough, and then transplanted on to a coral reef.

Figure 5-3. A coral nursery in Vava’u, Tonga

Photo Credit: Andrew Bruckner

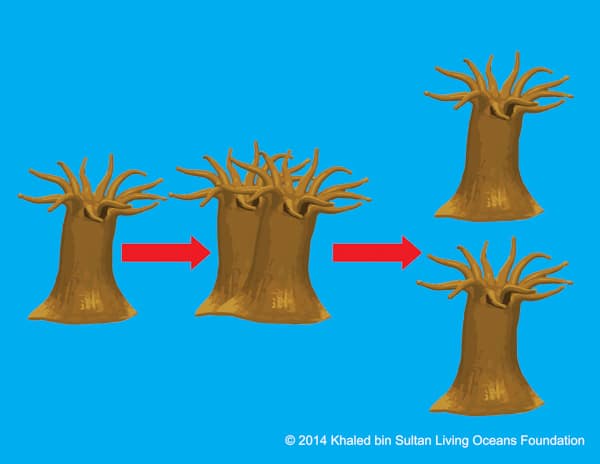

- Budding (figure 5-4): This category of asexual reproduction is found in all colonial corals. Budding occurs when a portion of the parent polyp pinches off to form a new individual. There are two ways in which this occurs:

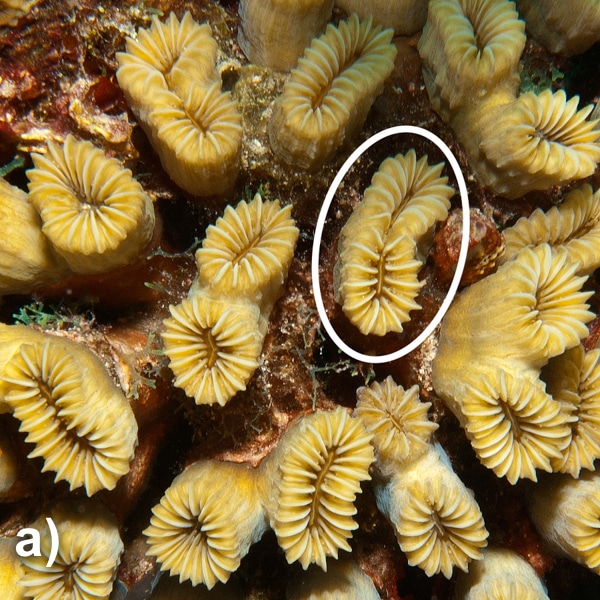

- Intra-tentacular: Buds form from the parent polyp’s oral disks, producing same-sized polyps within the ring of tentacles (figure 5-5a).

- Extra-tentacular: Buds forms outside the parent polyp’s ring of tentacles, producing a smaller polyp (figure 5-5b).

Figure 5-4. Coral budding

Figure 5-5. a) Intra-tentacular budding; b) Extra-tentacular budding

Photo Credit: Ken Marks

- Fission: During early developmental stages, some coral colonies have the ability to split into two or more colonies. This sometimes occurs with corals from the Family Fungiidae, the mushroom corals (figure 5-6). They are solitary corals that can decalcify, or break up, their skeletons, creating two pieces and then growing their other half back. Other similar types of reproduction occur in Fungiids. They can decalcify part of the skeleton forming acanthocauli (juvenile polyps formed asexually). These polyps grow on top of their dead parents and eventually break off into individual polyps.

Figure 5-6. Mushroom coral undergoing fission

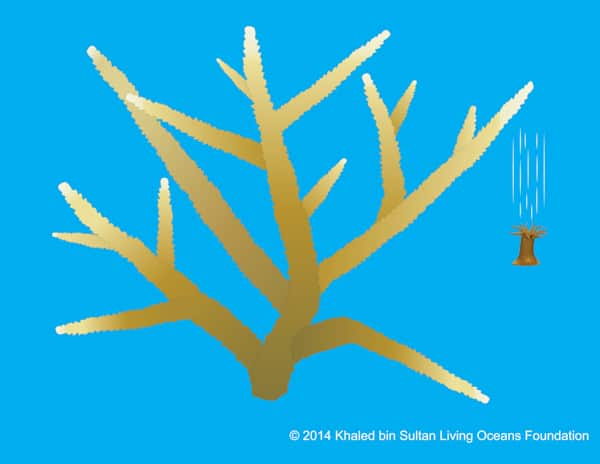

- Bailout (figure 5-7): When a single polyp abandons its colony and settles on the substrate to create a new colony. Sometimes this is due to a stressful event such as coral bleaching (Sammarco 1982).

Figure 5-7. Polyp bailout of a staghorn coral

ATTRIBUTIONS & CITATIONS

ATTRIBUTIONS

Figure 5-2. By Haplochromis [Public domain], 16 February 2007 via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AStony_coral_spawning.jpg.

Figure 5-7. For use of staghorn coral vector. By Tracey Saxby, Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (http://ian.umces.edu/imagelibrary/).

CITATIONS

Babcock, R. C., Wills, B. L., & Simpson, C. J. (1994). Mass spawning of corals on a high latitude coral reef. Coral Reefs 13: 161-169.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA). (2011). Coral Reproduction. Retrieved May 16, 2014 from http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/about-the-reef/corals/coral-reproduction.

National Ocean Service. (10 February, 2014). Coral Spawning. Retrieved May 16, 2014 from http://flowergarden.noaa.gov/education/coralspawning.html.

Sammarco, P. W. (1982). Polyp bail-out: An escape response to environmental stress and the new means of reproduction in corals. Marine Ecology Progress Series 10: 57-65.

Szmant, A. M. (1986). Reproductive ecology of Caribbean reef corals. Coral Reefs 5: 43-54.