Throughout the past three weeks, the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation, Bahamian researchers, and other collaborators experienced a unique opportunity to study the shallow marine habitats of Cay Sal Bank, Bahamas. Cay Sal Bank is a submerged platform that lies relatively close to the Florida Keys and Cuba, yet is remote, difficult to access and relatively un-impacted by man. Over 99% of the bank is submerged, ranging in depths from 5-12 m, with a narrow fringe of emergent land, comprised of small sandy vegetated islands and lithified sand dunes, surrounding parts of the central lagoon. Strong tidal currents, high winds and waves, frequent hurricanes and other forces of nature have created harsh conditions that have weeded out weak species. However, those organisms that survive under these harsh environmental conditions are flourishing.

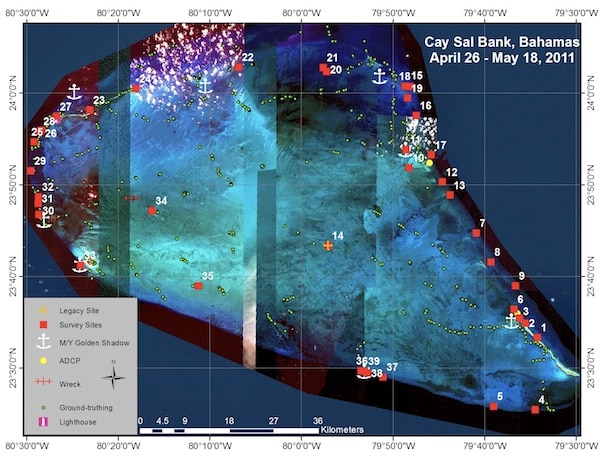

While previous descriptions of the marine habitats of Cay Sal Bank noted extensive seagrass bed communities and relatively depauperate and poorly developed reef systems, our extensive small-boat surveys using high-resolution satellite imagery to navigate, sophisticated acoustic measurements of the seafloor, and tethered underwater video and still images, revealed diverse geologic features and unique habitats shaped by these historic structures. We identified numerous sink holes, blue holes that extended to over 100 m in depth, perfectly circular seagrass beds that formed on top of sediment-filled blue holes and around man-made objects such as ship wrecks, aircraft and abandoned oil exploration equipment, scoured hardground areas, oolitic sand shoals and moving sand waves.

In addition to classic western Atlantic spur-and-groove reef systems that have developed around the outer portions of the marine habitats of Cay Sal Bank, unusual coral and sponge patches occurred within the bank, each differing in structure and species assemblages. One particularly intriguing area, at depths of 7-8 m, consisted of small coral bommies with many species of reef building corals and dense, colorful sponge assemblages. These sponges consist easily of over 50 different species, forming twisted ropes, fluorescent blue and yellow tubes, barrels, bright orange crusts, erect branches and vase-shaped structures intertwined with tree-like soft corals and massive and plating stony corals.

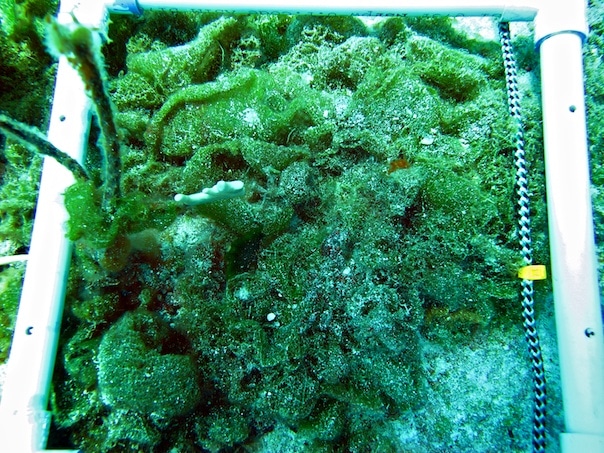

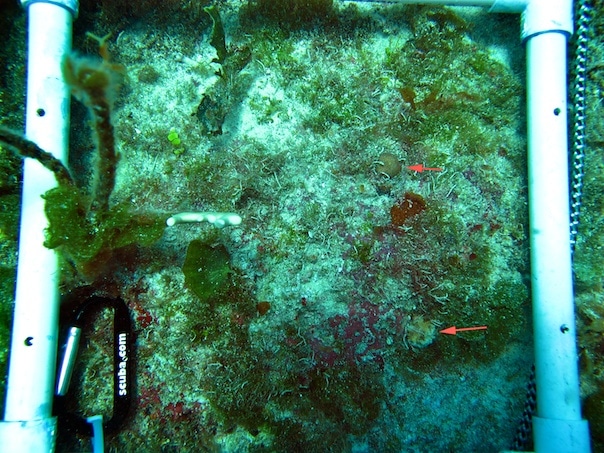

From the surface of the water, many of the shallow marine habitats of Cay Sal Bank appeared to be biologically impoverished, with little living coral and proliferate growth of fleshy seaweeds, better known as macroalgae. Of significance, much of the bottom was covered by green, lettuce-like fleshy Microdictyon algae, brown ruffled Lobophora algae and Sargassum, often forming accumulations 10-30 cm thick in sandy areas between the reef structure. Macroalgae like this is generally considered detrimental to the reef, because it grows faster than stony corals, can smother living corals, and it prevents settlement and recruitment of new corals. Yet, it was easily detached, and underneath, the reef substrate was bright pink due to encrustations of crustose coralline algae; a beneficial algae which is known to attract coral larvae. In fact, most reefs had unusually high numbers of small recruits and juvenile corals, which were undetectable until the algae were removed.

Larger corals, especially the dominant frame builders such as mountainous star coral (Montastraea spp.) had suffered extensive mortality in the past, especially during bad coral bleaching events in 1998, and possibly more recent periods of high sea water temperature.

This is similar to what is happening around the Caribbean, yet these corals in the marine habitats of Cay Sal Bank demonstrated unusually high resilience, with numerous smaller (juvenile) colonies of these species, sexual recruits (which have been rarely observed in the past) and remaining portions of the colonies, referred to as tissue remnants, surviving and progressively re-sheeting over the old denuded skeleton. What was also intriguing was the large numbers of small corals of other species that were present, even in scoured hardground habitats where currents, wave surge and storms are most intense. The presence of a high number of young and small corals, as well as the surviving patches of tissues on these larger framebuiilding corals both suggest the reef communities are rebounding from past disturbances.

Stresses to the coral communities are still present, however. A bright orange sponge that bores into coral skeletons, slowly eating away at the skeleton and killing the live tissue, was unusually abundant in most locations. It is unclear why, as these aquamarine waters are crystal-clear, with visibility often exceeding 100 feet, as a result of low nutrients, little sediment input, and an absence of land-based pollutants like that seen in reef communities near populated areas.

Coral diseases, while rare in most areas of the marine habitats of Cay Sal Bank, were observed on some of the larger remaining mountainous star corals, especially on deeper reefs at the shelf edge, where these star corals were still a dominant component of the bottom. The disease of most concern to the Caribbean right now, which was also observed here, is known as white plague. This disease has been reported from most reefs throughout the Caribbean at increasing prevalence and severity over the last decade, and in other locations it has been the number one killer of these and other species of corals. Even though white plague was present on Cay Sal Bank, no severe outbreaks were seen.

Besides competition from algae, the other threat to corals was a coral eating snail known as Coralliophila. These snails are unusual in that they eat coral tissue and yet they lack a radula, which is a tooth-like structure found in most other snails. They also change sex, starting out as males and becoming female once they achieve a certain size. These snails have become increasingly common in other locations, and they tend to grow very large when their preferred host, elkhorn coral, is abundant. On Cay Sal, most were 5-15 mm in diameter and normally cause little damage to their host, primarily consuming coral mucus. There were occasions, though, where aggregates of 10-15 snails were observed on the margin of a coral and a prominent white patch of denuded coral skeleton was seen. One of the reasons these snails are relatively rare in the marine habitats of Cay Sal Bank may be due to the high abundance of large lobsters, one of the coral-eating snails main predators.

Fish communities were diverse, but highly variable between sites. Several species that occur in other locations in the Bahamas were absent or rare, especially those that use mangroves as a nursery area; mangroves do not occur on the bank, except for a few areas on Cay Sal Island that are not located near the water. As a result, we saw few Nassau grouper and low numbers of snappers on outer reef sites, and most reefs had only one or two large black or yellowfin grouper. We know this is not due to overfishing, as very little fishing occurs on the bank.

What was surprising was the large schools of gray snapper, lane snapper, schoolmaster and many species of grunts on the top of the bank, where fish aggregated within grassbeds, especially around shipwrecks, submerged aircraft and other high relief structures. It is unclear how these species became established here, as the strong currents may restrict transport of larval fish and their primary nursery habitat is absent. Herbivores were fairly common, yet there was an absence of large schools of surgeonfish and large parrotfishes. Instead, large numbers of small parrotfish, smaller groups of surgeonfish, and many juveniles were found, including the greenblotch parrotfish which is usually less common. The presence of lionfish was also notable for the area. Yes, they are here, like elsewhere in the Caribbean, but their abundance is significantly lower. Usually the survey team found only one or two individuals on a dive. Over the entire mission, the total number of lionfish we observed over the entire expedition is probably less than a scuba diver might see during a single dive off New Providence, Bahamas. Nevertheless, those lionfish we observed were comparable in size to the largest typically observed in the Caribbean.

In addition to extremely large lobsters and several observations of large Mithrax crabs, queen conch occurred in very high numbers in nearly every habitat we examined, including grassbeds, hardground areas, sand flats, and on reefs. These mollusks usually eat small plants and algae that settle on the grass blades (epiphytes). Unusually, on Cay Sal Bank they were feeding on the green lettuce-like algae that covered much of the reef, something that has never been reported. Whenever we found large aggregations of conch, this algae was cropped close to the substrate, and if conch were absent, it formed mats up to 15 cm in height.

Our Cay Sal Bank Research Mission was ambitious, productive and a huge success. We accomplished more than we anticipated, being blessed with calm seas, clear water and sunny days. We had a dedicated team of researchers, including scientists from the United States and the Bahamas who worked extremely hard and collected a lot of comparable information on the habitats, organisms and resilience of Cay Sal Bank. Scuba divers characterized the distribution, cover, population dynamics and health of important reef building corals, how they varied among different habitats, and linkages between their occurrence and health and other plants, fishes and invertebrates. The information we collected will be analyzed in the upcoming months, and will result in numerous outputs, including detailed high-resolution habitat maps that can form a framework for marine spatial planning, a marine Atlas, and other products. Our surveys highlight changes that are underway in a previously disturbed location – positive changes that are translating into an upward projector of reef recovery. By using our results and tools to enhance the conservation and management of the marine habitats of Cay Sal Bank, this precious resource can flourish for enjoyment and benefit of future generations of Bahamians and the world.

I am indebted to our science team for their hard work. Special thanks for the logistical support and facilities provided by the Golden Shadow Officers and Crew, all of whom worked long hours leading up to the research project and each and every day of this mission to ensure the comfort and safety of our team, and contribute to the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation’s mission of ocean conservation. The gracious financial support and state-of-the art research ship provided by HRH Prince Khaled bin Sultan made this Expedition possible and for his generosity and dedication to coral reef conservation, we are forever grateful. The Global Reef Expedition is off to a magnificent start! Next stop: St. Kitts and Nevis.

Dr. Andrew Bruckner

Chief Scientist, Living Oceans Foundation

May 18, 2011

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and our team members.

(Images/Photos: 1. Amanda Williams; 2-10. Andrew Bruckner; 11. Liz Smith)