The most critical part of creating benthic habitat maps is the ground-truthing process for several reasons. First, exploring the research site improves the producer’s understanding of the landscape being mapped, thus allowing them to assess the maps qualitatively as they are being produced. Second, the field data gathered by the ground-truthing team is used to fine-tune parameters in statistical models, enabling the models to reliably predict the occurrences of different habitats within the imagery. A major component of the statistical modeling for mapping is collecting information throughout the study area. The field effort is often guided by the map maker as they must visit all of the visible landscape features, especially those that are not immediately recognizable. Visiting these unknown features often leads to surprising observations with important implications. Such an event happened during the ground-truthing of Scilly atoll in the Society Islands of French Polynesia.

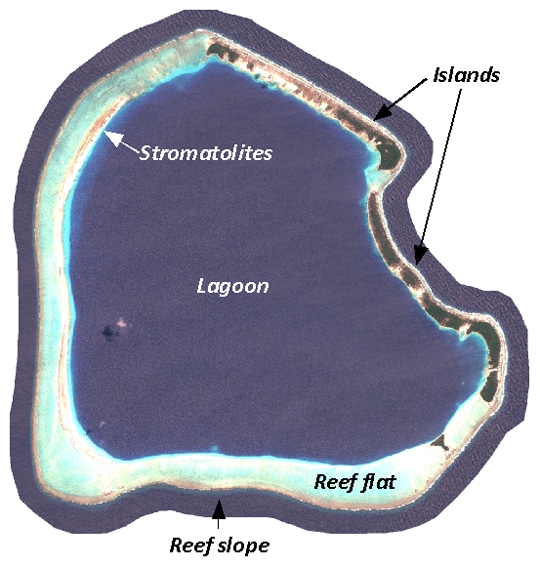

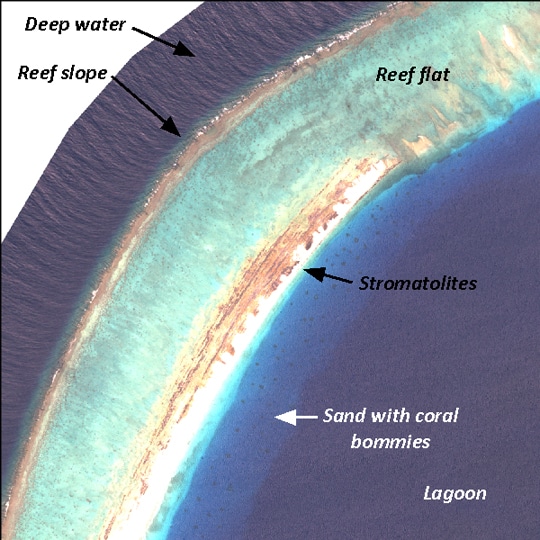

At a first glance of the satellite imagery, Scilly appears to be a standard atoll. There is a large, deep lagoon encircled by a reef flat transitioning into a coral-covered reef slope. However, a particular landscape feature stands out within the satellite imagery. From this bird’s-eye-view, there appears to be lithified sand dunes (i.e. loose grains of sediment converted to rock) between the reef flat and lagoon.

The ground-truthing team visited this feature to confirm this observation, but what they found was much more interesting. It was a large expanse of stromatolites.

Stromatolites are laminated structures formed when microbial mats, often composed of cyanobacteria, trap and cement sediments into rock. Some of the earliest fossil records are those of stromatolites. They take on one of several morphologies, such as conical, stratified, branching, domal, or columnar.

Stromatolites were common in the Precambrian, a geologic Supereon that accounts for 88% of geologic time, but they are rare in the Modern due to the development of burrowing and grazing life forms. Today, they are found primarily in locations with hypersaline conditions, such as lakes or marine lagoons, which prevent larger animals from grazing on the microbes.

Two of the best examples of modern stromatolite formations are found in Shark Bay, Western Australia, and Exuma Cay, Bahamas. In Pavilion Lake, Canada, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), and several universities are studying the stromatolites to assess how environmental conditions influence microbial life in an effort to understand how life on other planets may develop.

In French Polynesia, stromatolites have been observed in several atolls, and the finding of a large extent of stromatolites, which is observable in the satellite imagery, has several implications. The structures are delicate, and the presence of this large expanse indicates that the microbial mats are rarely disturbed. This is important in a geologic perspective because the microbial communities contribute to the creation of rocks on which islands and sand cays can begin to form.

Scilly is thus a great example of multiple biological processes driving geologic activity and shaping those landscapes observed in the satellite imagery.

(Photos/Images by: Jeremy Kerr)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members.

One Comment on “Rare Fossil Formations”

Leigh

Thank you so much for writing this article! I was on a sailing trip to Tikahau in February and I could not believe what I was seeing when I found stromatolites. I wouldn’t have know about them without having seen them in Western Australia ten years before. I’m not sure my friends believed me when I told them we were looking at ancient living fossils. Thanks for your research and protection of our ocean and our amazing home!