Expedition Log: Cook Islands – Day 6

We’ve seen a lot of unusual and colorful creatures that attach to the surface of a coral, bore a hole into its skeleton, or become encased by the coral as it grows. Most commonly, these are polychaete worms (the colorful Christmas tree worms and feather duster worms), bivalve molluscs (boring clams and giant clams), crustaceans (crabs and shrimp), and echinoderms (boring sea urchins). One of the more unusual is the worm snail, also known as the vermetid gastropod. Worldwide, there are about 150 species of gastropods in the family Vermetidae.

Vermetids can be confused with tube-dwelling polychaetes, as they produce a similar thin, hard tube that coils around a rock or other hard object. Yet they have a shell that is similar to other molluscs, consisting of three layers with a shiny or glossy inner surface. Also like other snails, they have a pair of tentacles, a small foot and a thin operculum attached to the foot that is used to seal the shell opening when disturbed.

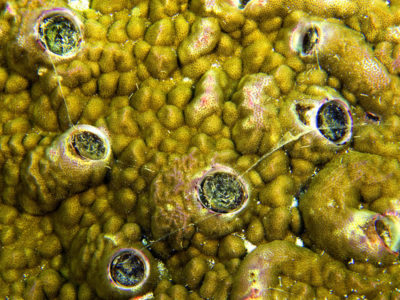

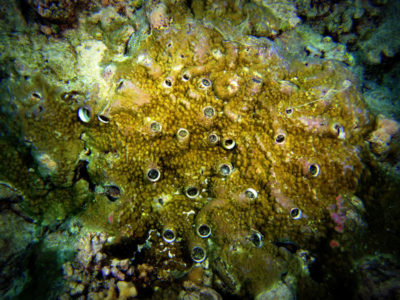

In Aitutaki, the Cook Islands, vermetid gastropods were commonly seen embedded into massive coral colonies, especially Porites. In some cases there were several dozen within a single coral.

Unlike other sedentary and sessile molluscs, worm snails do not filter the water to capture their food. Instead they secrete a mucus net from a gland near their foot. This net can be several meters long in some instances, and may be draped over the coral. Once the sticky net traps a sufficient amount of plankton, the snail retracts the net and consumes its catch.

Dendropoma snails and their mucus nets on Porites.

It would seem that these gastropods are harmful to the coral, stealing the food that may be otherwise caught by the corals tentacles, yet they appear to cause little harm to their host. All of the corals we found that contained worm snails appeared healthy.

Whenever we found these snails, every living coral in the area contained dozens of animals. The tendency to aggregate may be explained by their life history. Unlike many other marine invertebrates, their larvae do not spend time drifting in the water column. Instead, the male releases packets of sperm which are captured by the mucus net of the female. Eggs are fertilized internally and small snails emerge from the tube, crawl across the bottom for a short distance and then cement themselves to a coral.

Like corals and other organisms, they are sensitive to environmental stressors. In French Polynesia, scientists have just witnessed a large scale die-off of these molluscs. The cause of death is yet to be determined. Fortunately, during our surveys in the Cook Islands they seem to be flourishing.

Photos: Andy Bruckner

One Comment on “Worm snails”

Cathy

What happens to the mucous net once the worm retracts it? I read that captured organisms are consumed and I infer that the net is also consumed or absorbed, but then what? Is the mucous reused or excreted as waste?